Vehicle

Assembly

Building (VAB)

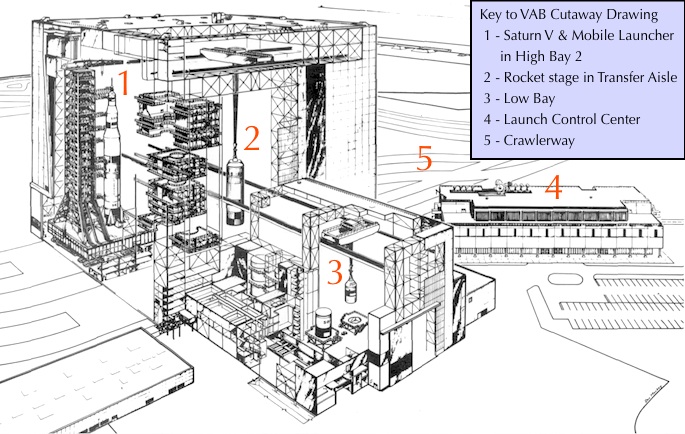

The Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB) and Launch Control Center (LCC) are the heart of Launch Complex 39, and are geographically in the center of Kennedy Space Center.

The Vehicle Assembly Building can be described with numbers and words and superlatives (e.g., "at 525 feet tall, it is the tallest building in the US outside of an urban area"), but words and numbers cannot adequately convey the enormity of the building. Seen from the outside, without any other tall structures nearby with which to compare it, its true scale is difficult to discern.

From the inside, one begins to appreciate the volume encompassed by the structure. One gets the impression of vast amounts of open space, in which the Apollo/Saturn launch vehicles and Space Shuttles were stacked. And yet, there are offices at all levels throughout the building. At the peak of the Apollo program, nearly 3,000 people worked inside the VAB.

The tallest section of the building consists of four "High Bays," each of which was originally intended to house a Saturn rocket under construction. Three High Bays were eventually built out, for stacking of up to three Saturn V vehicles at a time, with the fourth High Bay reserved for potential special use. High Bay 1, in the southeast corner of the VAB, and High Bay 3, in the northeast corner, were used for most of the Apollo missions. The diagram above shows a Saturn V being stacked in High Bay 2.

The High Bays are so huge that each one could accommodate the Secretariat ("monolith") Building of the UN Headquarters. Everything that sat on the launch pad - the Mobile Launcher Platform, the Launch Utility Tower, and the Saturn V rocket - longer than a football field - fit into just one of the High Bays. And at times there were three Saturn V rockets under construction simultaneously in the VAB.

Most of the office space in the upper levels of the High Bays held the instrumentation needed to check the functionality of a vehicle's systems as it was being erected. There were five pairs of movable platforms in each High Bay, which could encircle the vehicle as it was being worked on. Contractor offices were on the floors closest to their particular stage - i.e., Boeing's offices were nearest the S-IC, North American at the levels near the S-II, Douglas near the S-IVB, and IBM near the Instrument Unit.

A “Crawlerway” of crushed stone leads from the VAB to the Launch Pads, 3-1/2 miles away.

Not just a building

"The VAB is not so much a building to house a moon vehicle as a machine to build a moon craft. The Launch Control Center that monitors and tests every component that goes into an Apollo vehicle is not so much a building as an almost-living brain."

-- Max Urbahn, Lead VAB Architect

The VAB at the Height of the Apollo Program - August 1969

The photos below were taken by my father, John A. Ward, Jr., on a VIP tour of KSC in early August 1969. At the time of his tour, the Apollo 11 astronauts were still in quarantine in Houston, having returned from the Moon less than two weeks earlier. The VAB was a hive of activity, as the Apollo 12 and Apollo 13 launch vehicles were both being assembled and tested.

Upon entering the VAB, people immediately look up and say, "Wow!" as they crane their necks to see how high the ceiling is. What they quickly learn is that they are only in the Low Bay, where the various stages of the Saturn V were brought in horizontally from a barge.

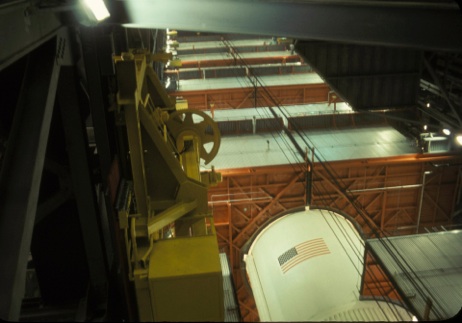

Once inside the VAB, the components of the Saturn V would be moved into the Transfer Aisle, which ran down middle of the building. There are two High Bays on each side of the Transfer Aisle. Here, one can look all the way to the ceiling of the tallest section of the VAB, more than 50 stories up. A 250-ton crane hoisted each one of the Saturn V’s stages into a vertical position and transferred it into one of the High Bays.

Walking into High Bay 3 from the Transfer Aisle, you are face-to-face with the largest launch vehicle ever built by the United States, the mighty Saturn V. The vehicle is being erected on the deck of a Mobile Launcher. Note the moveable work platforms that girdle the Saturn V during assembly and testing. To give a sense of scale in this photo, the white first stage of the Saturn V, with the US flag emblem, is 33 feet in diameter. The US flag is about 130 feet above the floor where my dad was standing.

Looking farther down the Saturn V, we see the “business end” of the S-IC stage. The designation “S-IC-7” identifies this as the Saturn V for the Apollo 12 mission, which launched in November 1969.

Sharp-eyed viewers will note the red-painted areas above the white conical engine fairings (e.g., above the sliver fins with marked with “C” and “D”). This shows that the forward ends of the engine fairings were not in place at this time. During flight, when the S-IC's fuel is expended and it is cut free from the S-II stage, retrorockets inside each of these fairings fire forward to help pull the expended stage away from the vehicle.

Another view of the base of the Saturn V, sitting on the Mobile Launcher. It is interesting to note that the workers in the foreground, at the edge of the Mobile Launcher, are more than 60 feet closer to the viewer than is the base of the vehicle. Note one of the holddown arms in the center of the photo. This would keep the rocket on the launch pad for the 8.9 seconds between ignition and liftoff, while the engines built up thrust and stabilized. The yellow structures with circular tops with openings in them, two to the left of the vehicle and one two its right, are the covers for the Tail Service Masts, which provided propellants to the first stage and contained connections for electrical, hydraulic, and pneumatic systems between the S-IC and the Mobile Launcher.

There was another occupant of the VAB that day -- AS-508, which would become better known to the world as Apollo 13. The race to meet President Kennedy’s challenge of getting to the Moon by 1970 meant that NASA needed to be prepared to throw as many Apollo missions at the Moon as possible in 1969 in case the first attempts failed. Indeed, Neil Armstrong has said on numerous occasions that he felt there was no better than a 50-50 chance that Apollo 11 would actually land safely. Had Apollo 11 failed, Apollo 12 could have flown in September 1969, and Apollo 13 was being readied for a possible November 1969 launch if necessary. Once Apollo 11 succeeded, the Apollo 12 launch was moved to November 1969 and Apollo 13 to April 1970.

The Saturn V launch vehicle for Apollo 13 is topped here by a “boilerplate” Command and Service Module. The actual flight articles were still undergoing assembly and testing in the O&C Building in August 1969.

We were put aboard chartered aircraft and flown to Norfolk for NATO briefings and a luncheon aboard a new nuclear aircraft carrier, then to Houston for a full day NASA briefing and tour and a sneak preview look at the moon rocks bought back only two weeks before by the crew of the first lunar landing. This was followed by a full day at Cape Kennedy and a VIP tour of the facilities. We received the whole treatment, and I don't remember any of my classmates who did not grow a little vain as a result of the experience. Pretty heady stuff for an old paramilitary type...

-- John A. Ward, Jr.

(c) 2012 Jonathan H. Ward